The New York Times recently published an article about a new trend in which companies are offering whole body MRI. The entire body is imaged inside the big magnet of a magnetic resonance imaging machine. The idea is that imaging the whole body can show hidden abnormalities that the patient doesn't know they have, so that something can be done about them sooner rather than later.

My purpose here is to address the most persistent point of view I see expressed by patients in discussions of this topic, namely: Why should anybody argue with me, or even try to stop me, from getting a test on my body if I can afford it, and want to know everything I can about what might be going on inside me? What could be wrong with looking inside the whole body? Knowing is always better than not knowing, isn't it? Especially if it might save my life.

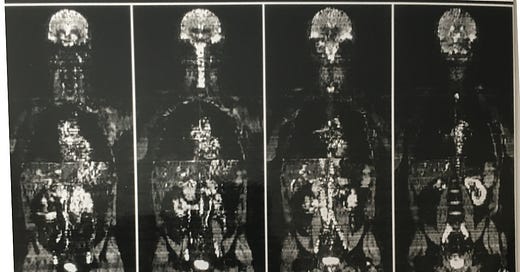

As it happens, in 1997 I was the first physician to publish an article on whole body MRI in a clinical journal. The illustration accompanying this post is one of the first images from my research. It's possible that's me up there; I spent many hours inside the magnet bore during that project. The scanner technology at Yale happened to be more advanced than at other institutions at the time. Along with my colleagues I showed how a survey of the entire body could be obtained in less than 18 seconds, and in a subsequent paper how metastases from breast cancer could be detected earlier than under the existing conventional staging protocols. Unfortunately, soon the company's fortunes changed and the scanner was removed. Other machines were not capable of the same rapid imaging; scanner capabilities have caught up so that it is now feasible and image quality has improved substantially.

Let me begin by saying that I endorse bodily autonomy and would never oppose an individual doing whatever they want in terms of gathering information about themselves – to the extent that doing so does not impose obligations or hazards on other people or society. (More about this caveat below.) This is not to say that I think doing so is always wise.

First a note on cost. Unlike nearly every public discussion on medical matters in this country, this one is not going to revolve around money. I will try to answer the question of what to do, and leave it to others to discuss whether it makes sense to pay for it. Without understanding why we're doing something we can't decide whether to pay for it. To do otherwise is to put the cart before the horse. Anyway I'm not qualified to write about economics.

Here is a crucial concept to understand before going any further: the physician (in this case the radiologist) starts the whole process of looking at a patient's imaging study with some preconception of what he or she expects to see. This is more formally called the "pretest probability", and can vary depending on which body part or disease we are talking about, and on various factors in the patient history. For example if the patient is a long time heavy smoker, the pretest probability of lung cancer is much higher than in a never-smoker. This is a complex landscape; many pretest probabilities exist at the same time in a given patient. Age and gender contribute as do many other aspects of the "history", that is, the patient's story past and present. If the story is that the patient has no known predisposition to disease and this is a screening test, then we are going to expect that everything is normal, and that if we see anything surprising we will be disposed to think it benign, because various benign conditions and variants are far more common than most non-benign ones. We are disposed here; we have not concluded yet. If instead we know there is a history of an aggressive cancer, now seemingly resolved, then if we see a small nodule in the lung, and we can show it is new we will be very worried. In the absence of such a history we will not worry much or at all, depending on the specifics. The importance of pretest probability seems to be lost on people who are not used to making decisions involving diagnostic tests.

In other words, the images alone do not always contain the answer. Getting to an answer depends on a synthesis of the imaging appearance with the underlying disposition towards particular diseases as suggested by the history, previous imaging, and other factors.

When an imaging test reveals something unexpected, the first step for the radiologist is to determine whether it is an incidental finding, an anatomic variant, or an imaging artifact. If a finding can be dismissed as not of clinical significance, it can be called an "incidental" finding (although confusingly this term can also mean a finding that is discovered unexpectedly while looking for something else and is not necessarily clinically insignificant). Radiologists play a major role here because they have a broad experience of many such findings and can confidently suggest that they not be pursued. Anatomic variants are a related phenomenon; these represent normal anatomy that is a little different from the usual, but is perfectly normal. These are easily mistaken for abnormalities by the uninitiated. Imaging artifacts are distortions of the image caused by technical factors; again radiologists have a crucial role here since in my experience non-radiologists seem to be almost wholly unaware of these problems.

An example of an incidental finding would be a calcified granuloma in the lung on chest CT (computed tomography, an x-ray procedure). A granuloma is a focus of inflammation that has healed as a sort of scar and can be recognized as such by its distinctive appearance on histology (microscopic anatomy of tissues). Sometimes calcium will precipitate out of the blood into these small round lesions. Granulomas are not cancer, and small ones do not have any chance of causing problems for the patient. They are evidence of prior inflammation, now resolved. It is true that sometimes they are clues to other problems; for example, they can indicate prior exposure to tuberculosis or histoplasmosis, and if the patient is having other problems, noticing the presence of granulomas might be of help in the differential diagnosis. But in and of themselves they are not dangerous, or as we say, they are benign. They are so common, and their appearance is so distinctive that to pursue them with a biopsy would be foolishly aggressive, and of no use, especially because biopsy of the lung has definite risks.

An example of a normal anatomic variant is an accessory spleen. Most of us have just one spleen, a relatively large organ in the upper left part of the abdomen, underneath the ribs and to the left of the stomach. The spleen has several functions, primarily in the maintenance of the blood and immune systems. In some people, other little round nodules can be scattered nearby, called splenules for "little spleens". These function like miniature spleens and can even increase substantially in size, to compensate after the spleen itself is removed. The point is that these can mimic metastatic deposits in the abdominal cavity. This can present difficulties in staging and diagnosis of certain conditions, like ovarian or colon cancer. Steps must be taken to ensure against misdiagnosis.

There are hundreds of such incidental findings and anatomic variants (and technical artifacts). The radiologist is responsible for recognizing them. But this is only the first step. What if the unexpected finding cannot be dismissed as any of these?

The next step in many cases is to look at previously performed tests, in particular imaging tests that show the same anatomic region, to see if the finding was present previously. Many potential follow-up tests are avoided by this means; conversely, if a change is seen then a further test can be recommended, because then the likelihood the finding may be clinically significant has increased.

If we've gotten this far, we have an imaging finding that we cannot explain away. So we have to now come up with a differential diagnosis, a list of possible diagnoses. Each diagnosis will have a pretest probability attached to it, and often each will require further evidence of some kind to "rule in" or "rule out". The most important tests to do are the ones that eliminate the probability of the most serious conditions. But before a test is ordered, the pretest likelihood of the potential disorder must be considered. If it is very low, and the test carries a risk, then holding off testing might be wise. Conversely if the probably of serious disease seems high, then a risky test can be justified. Practically speaking, a full differential diagnosis can be quite long, and many contributing factors can be unclear, so that doing enough tests to exclude every possibility but the correct one is not practical, even if possible. Surprisingly often the best course is to wait; physicians even have a saying for this: "the tincture of time".

Be aware that the sensitivity of a whole body MRI, that is, its power to detect abnormalities, is limited compared to more specialized or targeted scans and tests. An abnormality, even a major one, might be present but not detectable on the scan. No test is perfect. Diagnostic testing of all kinds, not just imaging, is beset by the problems of false alarms (false positives- a positive result when the disease is absent) and false reassurances (false negatives - a negative result when the disease is present). This deserves a post (or a book!) of its own. Suffice it to say that a minority of test results are not entirely clear ("diagnostic") on their own.

Of key importance is the type and focus of a test. In radiology, there are many factors to consider such as whether to use ionizing radiation, whether to inject contrast agent into the bloodstream, whether to thread a catheter into an artery, or to pierce an internal organ with a biopsy needle. Yes, radiologists do these things too. If your problem is shoulder pain, and you have an MRI of the whole chest done, the images of your shoulder are going to be quite suboptimal, and the pathology if any is probably going to be missed. Imagine how much worse this poor targeting is if you are attempting to rapidly image the entire body.

A related problem is that of specificity, that is, if an abnormality is seen, what exactly does it mean? Many disease processes lead to similar imaging findings. Another task of the radiologist is to try to distinguish among the often subtle differences between pathologies. In many case, some kind of further workup will be required if a more specific diagnosis is needed, as it often is to select the best treatment.

So, if you elect to have a whole body scan, how should you approach it? That is, what should your expectations be, and what should you do with the results?

Keep in mind the burden of knowing without doing. Some of us have a hard time living with uncertainty. If we know something has been seen, and decide not to do anything further, then if we are wrong we risk regret. But if instead we act, and find nothing of import, but injure ourselves (or our loved one) in the process, what then? All of the considerations above, which I have been able to outline in only the briefest of ways, must come under consideration. For almost everyone, even doctor-patients like myself, dealing with it can be overwhelming. This is why it should be thought about ahead of time, with the participation of a trusted physician.

In the end, a whole body MRI can impose obligations and hazards on other people and society, even if you elect to do it of your own free will, and pay for it. It imposes a risk on your physician by his or her having to deal with findings that arise on an imaging study suboptimal for the characterization of an abnormality, as often must be the case with even the most beautiful whole body MRI. The reality is that when an individual has a test that reveals something out of the ordinary – a "finding" – an obligation is created for the physician to resolve the matter one way or the other. A patient could of course absolve the physician from this, but why would they? To know which findings to pursue and which to dismiss requires expertise the patient doesn't have. It imposes additional costs on the health care system because the cost of follow-up workups are typically borne by insurance or Medicare, increasing costs for society. It runs the risk of leading to invasive and potentially harmful biopsies and other tests. If you are injured as a result, then your loved ones are injured as well to some degree, by definition. Keep these impacts in mind. Act on only those findings that are potentially serious. Accept that serious things might be present that you cannot see or cannot see clearly enough to justify acting. This imperfect knowledge can be difficult to live with.

My recommendation if you decide on proceeding to a whole body MRI is to agree with your doctor that you will pursue only the most potentially serious of observations. Resolve ahead of time that you acknowledge that every human being has flaws and unexpected quirks of their body, many of which usually escape notice, and that their significance is not changed by the mere fact of them being brought to light.

Insist that your doctor discuss the results over the phone or in person with the reading radiologist. Radiologists and ordering clinicians alike have unfortunately become unaccustomed to this kind of consultation so you must insist. Force them both to list for you what they think is important, and separate those concerns from the rest. Release your physician from the obligation of chasing every single finding no matter how minor. Ask if you were their loved one, what they would recommend? Then, if you trust their judgment, follow their lead.

If you don't, get a different doctor.

(Note: This essay is in reference to screening with whole body MRI. The technique can be used to great advantage for the staging and follow-up of disease, and I expect to see that use increase over time. But that use is distinct from screening. What is the big factor distinguishing these two uses? Pretest probability.)